Carried Ashore Maps

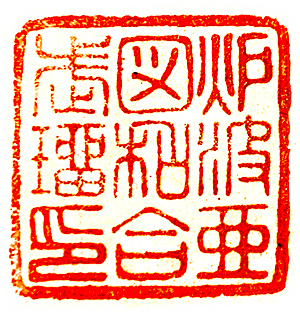

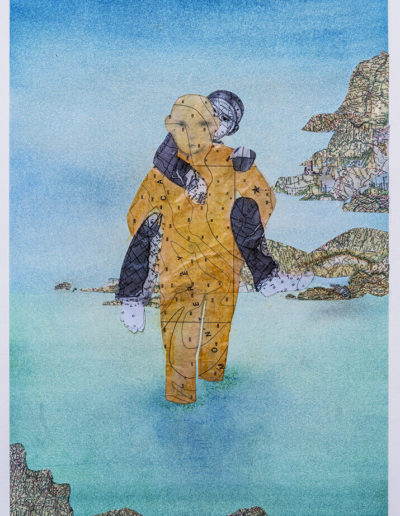

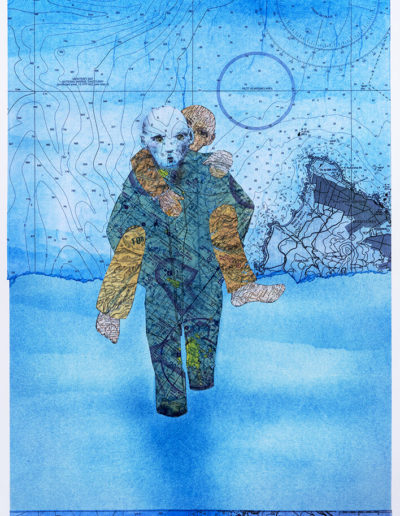

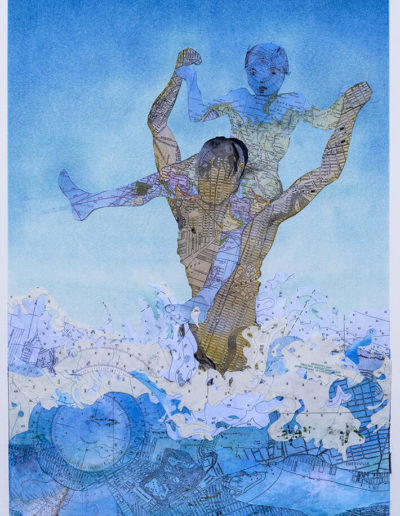

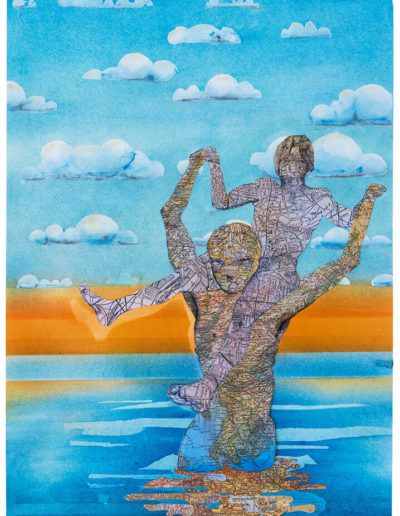

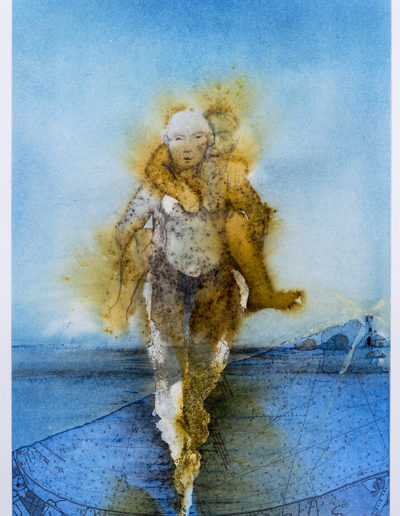

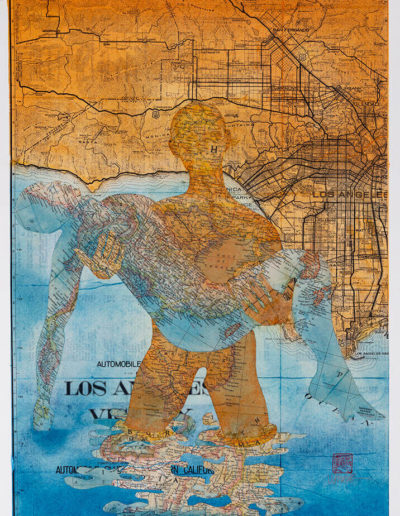

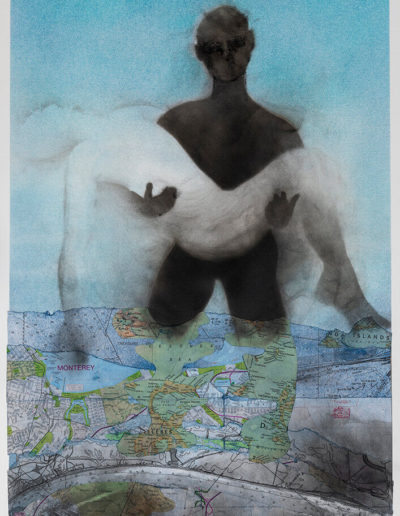

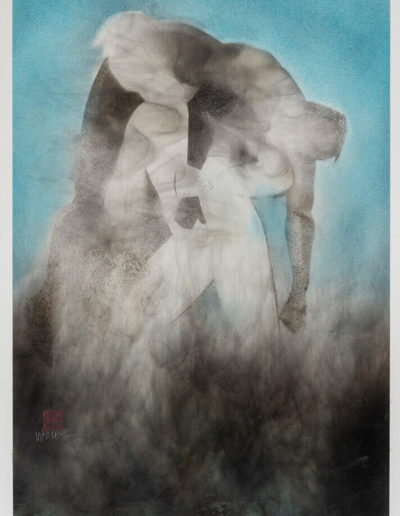

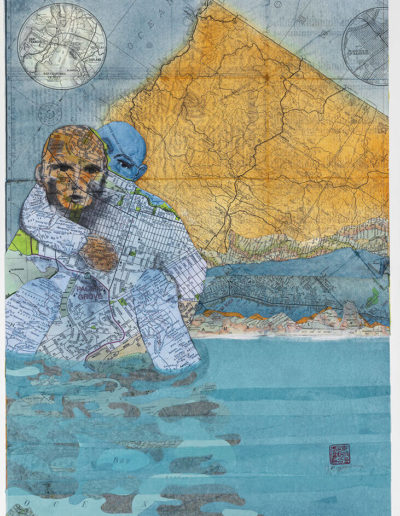

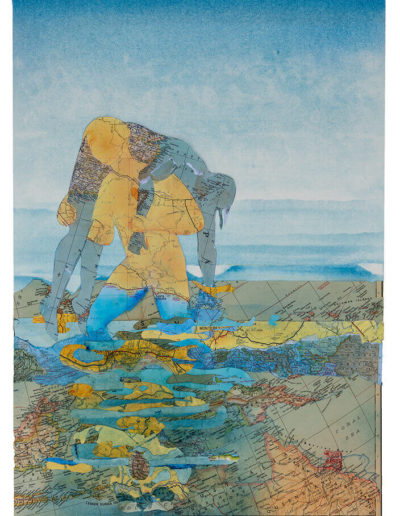

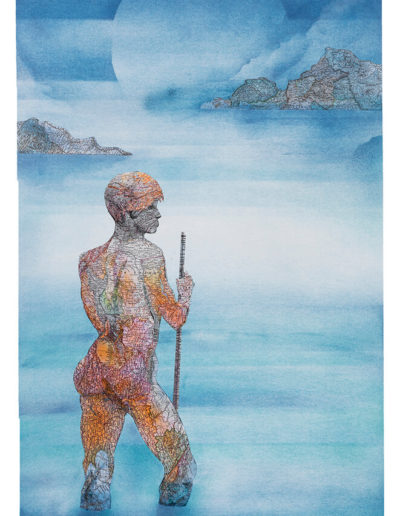

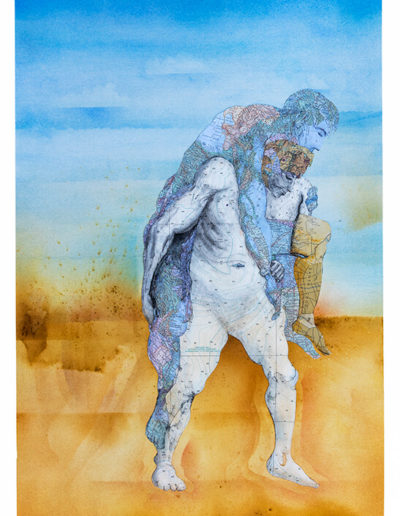

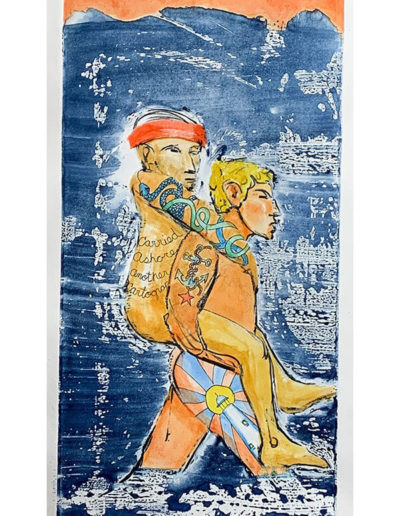

The series Carried Ashore/Another Cartography depicts one figure helping another through a major transition. The images are created by collage elements from vintage atlases, nautical charts and maps, soft pastel, gunpowder drawing and other elements on paper. Inspired by time on California’s central coast and current world events, these are not typical seascapes.

This series was awarded inclusion in Donald Munro’s Top 20 Cultural Events of the San Joaquin Valley 2018.

FOR ROBERT WEIBEL, A MAP OF THE WORLD WHERE PEOPLE CARRY EACH OTHER

At age 50, Robert Weibel shifted careers to become an artist. It’s been a fruitful and fascinating ride. In his new exhibition “Carried Ashore: Another Cartography” at Vernissage gallery, you get to see a brief retrospective of his work. You also get to delight in his newest fascination: using old maps, along with pastels, to create a series of works dominated by the image of one human figure carrying another.

Weibel’s collage technique is wonderfully precise and textural, and the feelings of depth that he achieves — and the ambiguity of the borders between his elements — adds to the impact.

He made a bang in recent years in the local arts scene, so to speak, with his popular “gunpowder” paintings. Now he’s moved on. Life is short, he says. (In fact, he lost one of his mentors and muses, the poet Peter Everwine, just a few days ago.) He wants to carry his creativity as far as it will take him. I caught up with the artist at Vernissage a few days before his ArtHop opening. (The monthly open house of galleries and studios in the downtown and Tower District neighborhoods runs 5-8 p.m. Thursday, Nov. 1; see the Fresno Arts

Council listing for details.)

Here’s our interview.

Question 1 :

First off, I’ve always loved maps. I used to spend way too much time as a kid looking through an old atlas at home. Tell us about your relationship to maps and how they fit into your new work?

I surveyed for logging roads and was on a crew making a topographic map in the Sierras with the Forest Service when I was a young man. I’ll never forget the feeling of watching the elevation lines being drawn creating a picture of the land I was standing on.

Here I was on one surface (ankle deep in pine needles) transitioning to another surface (topographic map). A couple of years ago I picked up a 1909 New Encyclopedic Atlas of the World at an estate sale in Cambria thinking I might use the illustrations on the old crumbling pages to wrap figures I was making.

I soon became enthralled with the maps themselves.

Such designations like “UNKNOWN REGION” marked a different time when there was more wonder. Robert Macfarlane wrote: “We are habituated to regard cartography as a science … But before it was a field science, cartography was an art.

It was an art that mingled knowledge and supposition, that told stories about places, and in which astonishment, love, memory and fear were part of its projections.”

Today with GPS, the wonder of maps may be fading like old books.

While working in my studio I constantly had to discipline myself from getting obsessed with a single city, or river, or coastline since I was simultaneously working with dozens of maps and parts of maps — nautical maps, aviation maps, Automobile Association road maps, National Geographic history maps.

They became wormholes of distraction from completing an image.

Question 2 :

You were drawn to the image of one figure helping one another, which is a recurring theme in these works, and you told me you had several inspirations: the plight of refugees trying to cross the Mediterranean; terrible flooding in Texas; and a famous work by Rafael. How did all these collide in your head, so to speak?

The idea of the image of one figure helping another has been on my back burner for decades — maybe from figure drawing and work in mental health, personal recovery, I’m not sure.

Recent headlines of folks struggling holding each other, whether in Texas high water or the island of Lesbos, the people were the same.

Looking at Raphael’s painting of Aeneas (“The Borgo Fire”) carrying his father out of danger is the same picture of one person helping another. There is a universal spiritual principle and practice of being of service to those around us.

Question 3 :

Why do you think you were so drawn to the ocean in these works?

The ocean is dark and dangerous, but she’s our mom.

Much of the wonder in my life has been by the ocean, from childhood abalone hunting to tea at Tate Ishi in Japan to snorkeling in Hawaii, to sketching the Piedras Blancas light station, The ocean is often about “passage” from here to there, through unknown and scary waters that can also be cleansing and renewing.

We came from the sea and it is in us. It is in our passion, our tears, in our bodies. We’re made of water.

Question 4 :

A lot of people still think of you as the “Gunpowder Guy,” but you’ve moved beyond that. Why?

Life is short. I have been given incredible emotional and spiritual and material gifts.

I’m one of the few that can make whatever art I choose, so I have a responsibility and obligation to try to explore something new.

Take some risks, make some mistakes and not crank out the same decor over and over because it gets approval.

I don’t have too much more time and there’s so much I have to learn and screw up and try again.

Question 5 :

Regarding the recurring carrying-figure theme, one thing you said to me just a few minutes ago really stuck with me: Sometimes we are the person who carries, and other times we are the person who is carried. What do you mean by that?

Sometimes only in retrospect can we see that helping one another actually helps us.

Ego can be a burden weighing us down. The practice of helping another can free us from our own self-centered worries.

It can lift us to a more peaceful and smooth place. I pursue this with limited success but I’m committed to keep practicing.

“We are habituated to regard cartography as a science… But before it was a field science, cartography was an art. It was an art that mingled knowledge and supposition, that told stories about places, and in which astonishment, love, memory and fear were part of its projections.”

– Robert Macfarlane